On the wisdom of loving imperfectly—what Eric Rohmer's films can teach us about our romantic contradictions

Rohmer's films are invitations to a more honest relationship with our own romantic natures.

“Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.” — Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

Our understanding of love is often shaped by grand, exalted romantic narratives.

These are narratives which have been handed down to us by generations of poets and storytellers. The unrealistic nature of these stories, however, make romantic love one of the least understood and misrepresented aspects of human life, and set us up for inevitable failure in our attempts at love.

Whether it is Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet, the medieval tale of Tristan and Isolde, or the story of Heathcliff in Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights, each tale ends in tragedy and ruin for the young lovers when the reality of their circumstances fail to match their idealized notions of love.

Eric Rohmer, the French New Wave filmmaker, offers us a different but, perhaps, more enlightened insight on the nature of romantic love.

The characters we see in Rohmer's films show us how—when it comes to our romantic desires—we are fundamentally dishonest with ourselves. We are routinely and predictably indecisive and engage in elaborate rituals of self-deception. Yet, to Rohmer, these are not merely character flaws; they are at the core of what makes us human.

With Rohmer, we find a less judgemental and kinder lens to understand our afflictions in the domain of love. The characters we see in his films are not good or evil, heroes or villains, but recognizable versions of ourselves—people who sometimes lie to themselves with extraordinary creativity, all in an attempt to make the burdens of life and love more bearable.

Film recommendations

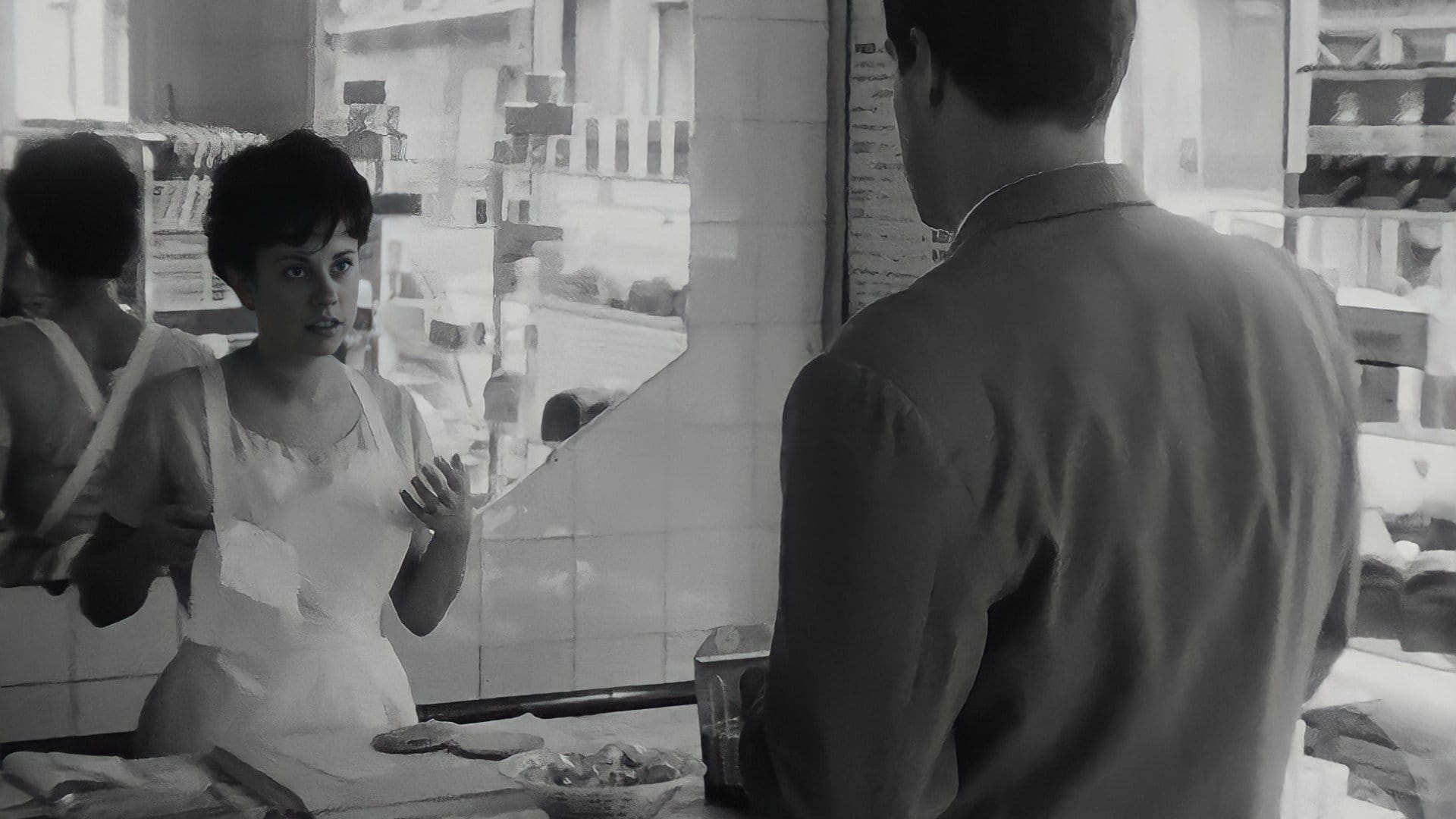

- The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1963)

- My Night at Maud's (1969)

- Love in the Afternoon (1972)

- Boyfriends and Girlfriends (1987)

- A Summer's Tale (1996)

We routinely deceive ourselves about our true romantic desires and motivations

The most convincing lies we tell ourselves are the ones about our own longings. It is a skill we have honed to perfection.

In The Bakery Girl of Monceau, we meet a young man who believes himself to be devoted to one woman. But when she suddenly disappears, he immediately transfers his affections to another woman—the titular bakery girl.

The young man does not see this as fickleness. He is convinced that he was meant to be with the bakery girl all along. But then, when it finally looks like the flirtations with his new romantic interest will turn into something more, his original object of desire reappears. He abandons the bakery girl without a moment's hesitation, constructing elaborate justifications for his decision.

We, as the disinterested audience, are able to see his actions as nothing more than an impulsive, hedonistic pursuit of pleasure. But this insight into his behaviour remains hidden to himself. He has constructed an internal narrative in which he is passionately pursuing true love, and he is none of the wiser to his actual motives.

Similarly, in Love in the Afternoon, Frédéric—a happily married man—frames his potential infidelity not as cheating or him simply giving in to lust, but as a philosophical inquiry into the nature of relationships and commitment.

Rohmer's characters use their abundant intelligence to transform any emotional impulse into a seemingly reasoned intellectual position. The tragedy (and comedy) of the situation is that it is their very intelligence which makes them more self-deluded, not less.

And what is true for Rohmer's characters is also true for us. The smarter we are, the more sophisticated our rationalizations become. We convince ourselves of almost anything, once we apply enough effort.

Random events and sheer chance shape our love lives more than careful planning ever could

Another powerful illusion we tend to believe is: we are the authors of our romantic stories.

We speak of "finding" love, of "choosing" partners, of "building" relationships. But Rohmer's films suggest a more humbling view—that we are often passengers of our own romantic destinies, subject to forces as random as the weather.

In My Night at Maud's, Jean-Louis has constructed a clear, unalterable plan for his romantic future. He will seek out and marry a woman he had once glimpsed at church; to him, it feels like destiny.

But unexpectedly, a snowstorm forces him to spend the night with Maud. Thrust into this situation—spending a night with an unknown woman—makes Jean-Louis question everything he thought he wanted from love. The entire trajectory of his emotional life almost takes an about turn due to something as ordinary as unpredictable weather.

The weather in My Night at Maud's is not merely a plot device; unforeseen events having a profound effect on characters is a repeated motif we see in Rohmer's films. Gaspard, in A Summer's Tale, drifts through an entire summer unable to choose between three potential romantic partners. He is "saved" from decision-making by external circumstances that resolve his dilemma for him.

The most poignant example is perhaps Félicie in A Winter's Tale, who loses contact with her greatest love through a simple error while taking down his address. For years, she maintains hope that they will somehow reunite. And remarkably, they do. Through pure chance. It is a happy ending that feels miraculous precisely because it acknowledges how often things depends on forces entirely beyond our control.

Relationship researchers have identified this phenomenon—the tendency to let circumstances determine our romantic fate rather than making conscious choices—as "sliding versus deciding." We often slide into cohabitation because the lease on a rent expires, into marriage because that's what out families tell us to do, and so on.

Rohmer's characters remind us that while we have constructed an elaborate mythology around romantic agency, much of finding love is actually about being in the right place at the right time.

We use sophisticated reasoning to justify emotional impulses we don't want to acknowledge

One of the first things you notice about Rohmer's characters is that they are extremely articulate about their feelings. (And, as we saw earlier, this articulateness is precisely what makes them so self-deluded.)

They do not simply stumble through their emotional lives; they analyze, intellectualize, and philosophize everything. Their intelligence becomes a tool for avoiding the true nature of their circumstances rather than confronting it.

The dinner conversations in My Night at Maud's serve as a striking example. The characters debate Pascal's philosophy, discuss the nature of faith, and explore questions of moral consistency. They sound impossibly sophisticated. But beneath this philosophical grandeur lies something much simpler: sexual tension and desire that nobody wants to acknowledge directly. The intellectual discussion is essentially a socially acceptable way to flirt.

This pattern repeats throughout Rohmer's work. Another example is Guillaume in Suzanne's Career, who justifies his cruel treatment of a woman by claiming she lacks dignity and therefore deserves his scorn. He is not being heartless; he is being educational. Delphine in The Green Ray justifies her refusal to compromise in love by claiming she is waiting for a mystical sign from the universe. And in Pauline at the Beach, the characters construct elaborate theories about love and sexual freedom to justify their messy affairs.

This reflects something that the psychologist Jonathan Haidt has identified as fundamental to human psychology: we are not rational creatures who occasionally feel, but feeling creatures who occasionally rationalize. We possess what researchers call "dual-process" reasoning systems — one fast, emotional, and intuitive; another slow, deliberate, and rational. The first system makes our decisions; the second constructs explanations after the fact for why those decisions were actually wise.

There is something oddly hopeful about this. If we are doomed to self-deception, at least we are creative about it. Rohmer's characters may be fools, but they are eloquent fools—and in their eloquence, we recognize something precious about the human capacity to find meaning even in our own contradictions.

The wisdom of loving our contradictions

What makes Rohmer's vision so valuable is not that it offers solutions to the problems of love, but that it accurately diagnoses what those problems actually are.

His characters are not failures of human development; they are examples of human development working exactly as designed. We are built to deceive ourselves, to be influenced by chance, to use our intelligence in service of our desires.

This might sound depressing, but it is actually liberating. Once we accept that we are fundamentally contradictory creatures—that we will lie to ourselves, be shaped by forces beyond our control, and use our minds to justify what our hearts have already decided—we can begin to have more realistic expectations of ourselves and others.

The goal is not to transcend these tendencies that come with being human. But to approach them with compassion.

When we catch ourselves constructing elaborate justifications for obviously selfish behavior, we can smile at our own predictability rather than pretending we are above such things. When we realize that chance has played a larger role in our romantic lives than we care to admit, we can feel grateful rather than diminished.

Rohmer's films are invitations to a more honest relationship with our own romantic natures. They suggest that wisdom lies not in conquering our contradictions but in understanding them—and perhaps finding them, if we are lucky, endearing rather than shameful.

After all, it is precisely because we are so magnificently inconsistent that love remains mysterious, surprising, and worth pursuing, even when we have no idea what we are actually pursuing or why. In our contradictions, we find our endless capacity for surprise—including the beautiful surprise of being loved despite, or perhaps because of, our beautiful contradictions.